As Howick and districts count down to the 175th anniversary, the Times continues its series by Alan La Roche giving readers a glimpse of life as it used to be. The countdown began at the 170th in 2017.

Early in 2020, the New Zealand Government stored pandemic equipment for an emergency occasion such as Covid-19.

Many families interviewed remembered the Spanish Flu of 1918. At the end of the awful Great War of 1914-1918, soldiers returned to a subdued welcome including some in Howick who later died of the ‘flu. At one stage there were 60 waiting to be buried in Howick. Our soldiers in France suffering battle fatigue, poor unsanitary living conditions, over-crowded tents and poor rations, succumbed quickly. There was no resident doctor in Howick.

Clarie Howie was asked to help the gravediggers dig more graves as they could not cope. Clarie was paid 25 shillings per grave in the Pakuranga Methodist graveyard in Pakuranga Road. He said the smell was awful. But the gravediggers said, “a stiff whiskey afterwards and you’ll be alright”. Edwin Roberts, another Pakuranga farmer, ran a shuttle service for prescriptions on his motorcycle from the doctor to the Otahuhu or Ellerslie pharmacies. One day he made five trips to Otahuhu on the rough metal roads. There was no pharmacy in Howick at that time.

New Zealanders blamed our Prime Minister William Massey and Sir Joseph Ward who were returning from Europe on the Niagara. The ship had passengers and crew suffering from the “simple influenza” as the politicians called it. The ship was not put into quarantine. This influenza killed more than 25 million people world-wide and 8600 in New Zealand of which more than 2000 were Maori.

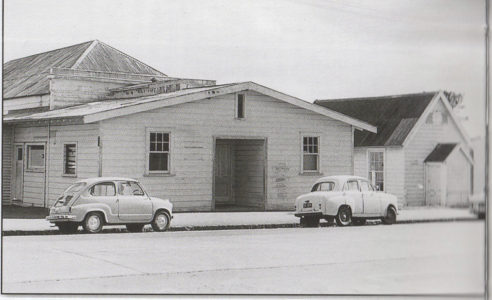

The Howick Town Hall in Picton Street, and Whitford Hall, were converted into isolation wards for ‘flu patients. Community volunteers nursed the sick, washing patients, boiling laundry bedding, providing meals and running messages all without power in Howick.

Candles and kerosene lamps were used. The Red Cross, Scouts and Girl Guides and teachers helped community volunteers. Schools, churches, hotel bars, race meetings and shops were all closed. Many doctors were still overseas treating war wounded.

It particularly affected 30 to 40-year-old men. Vomiting, diarrhea, pneumonia and death followed quickly. Some turned black, reminding some of the stories of the Black death plaque of the 14th Century. When the Armistice was announced in November 1918, there were some celebrations, but 268 died that day in Auckland from the ‘flu.

Pakuranga farmers closed off their farms. Whit Blundell on Butley Farm [in today’s Butley Drive] saw no visitors and the children stayed at home. They killed a sheep and fished for eels or sprats in Wakaaranga Creek.

Treatment of the flu was ineffective. Inhalation sprays of zinc sulphate and wearing a bag of camphor around your neck were recommended.

One Howick lady took up smoking to “kill the bugs”. The Government gave out small bottles of whiskey, brandy or stout to “stimulate better health” of poor people with sickness at home. Some gave frequent lemon drinks and bed rest to survive.

The crisis eased after two months. An inquiry was held and there were major changes providing electricity, treatment of sewage, better housing and reticulated water especially for Maori communities.

Today we have a free influenza vaccine for those over 65 and others considered at risk.

Alan La Roche

Howick Historian